This page

deals with the making of 'There's No Tomorrow',

the animated Peak Oil/anti-growth documentary, available

here.

This page

deals with the making of 'There's No Tomorrow',

the animated Peak Oil/anti-growth documentary, available

here.The inspiration for the film.

In November 2004, on the night of the final Bush/Kerry debate, Professor David Goodstein, Professor of Physics and Applied Physics at Caltech, gave a public lecture on the subject of Peak Oil and Energy.

Goodstein, who at the time was Provost of Caltech, explained the essentials of the issue, and the problems with the numerous alternatives to fossil fuels. By the end of the hour it was clear that the next few decades were likely to be difficult. Goodstein concluded the lecture with the following prediction:

"Human civilization as we know it will end, sometime in the 21st century."

He added that he hoped that making the prediction might alter the outcome of the prediction - in other words, the outcome is not set in stone, and there may still be time to prevent the collapse. Or as the proverb says:

"Unless we change direction, we are likely to end up where we are heading".

Even after Goodstein's lecture, doubts remained. What if his figures were incorrect, and the supply of oil was much larger than expected? What if decades or centuries of oil reserves remained, as some claimed? This question was resolved a few months later on viewing Professor Al Bartlett's video lecture: "Arithmetic, Population and Energy"

Professor Bartlett's mathematical explanation of the consequences of exponential expansion is relentless. Regardless of where humans stand on the graph of resource use, it was now clear that there were hard limits to growth - and that those limits would be reached, sooner or later - whether or not in our lifetimes.

Fast forward a few months, to early 2005: watching friends in a local Los Angeles Peak Oil group try to work a crowd of passers-by at an anti-war event. Handing out pamphlets as political actions might have been effective in previous decades, but in 2005 it seemed futile. Hence, the idea to animate a short introduction to Peak Oil - to condense the information for those who didn't have the time or desire to sift through dozens of websites and books.

Research and Development.

There followed many months of research, of websites, documentaries and books. Books, many written not by cranks, but by oil industry insiders, geophysicists and knowledgeable generalists. "Out of Gas" by David Goodstein; "Beyond Oil" by Kenneth Deffeyes; "The Party's Over" by Richard Heinberg and "The Long Emergency" by James Howard Kunstler, to name a few. In addition, sites such as theoildrum.com and energybulletin.net provided valuable ongoing analysis.

The original idea for the film was to be a funny pastiche of the pro-capitalist propaganda cartoons of the 1940s and 50s. These works are all in the public domain, making them an invaluable resource: "Going Places" (1948), "Meet King Joe" (1949), "Why Play Leapfrog" (1949), "What Makes Us Tick" (1952), "It's Everybodys Business" (1954) and "Destination Earth" (1956).

Those cartoons explained to the working and middle classes of post-WW2 America why capitalism and growth were good, and how oil provided the energy to make them possible. It seemed a natural idea in 2005 to reverse the story: what happens to this growth-based economy when the oil supply starts to decline? The plan to make a parody of the propaganda films was quickly abandoned, in favour of making a "sequel" - using the same storytelling style, imagery and animation, but with a very different message.

Each of the films was downloaded from the website archive.org, where they are freely available. Screenshots were taken of every scene, and a large visual library was assembled. Many of these would become the basis for the style and look of the film...in effect, they were used as "keys" to establish the visual style of the new work. Often, the original backgrounds were reconstructed, the characters erased from them, to allow them to be reused in a fresh scene. This was a time-consuming process, and took many weeks.

Production.

Some animation - of the oil production graphs - began tentatively in early 2005, and halted in late 2005 (due to being hired by a company that claimed intellectual property rights over all work by their employees, both at work and at home). Serious production began shortly after leaving that job, in March 2007, and subsequent sequences were completed in 2008 and 2009, with subsequent improvements until May, 2011. Although the gap from start to finish is ~6 years, there are about 2 to 3 years of total work involved.

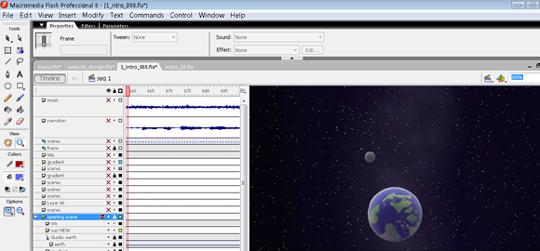

All of the animation was created in Flash 8. Only the storyboards were drawn on paper, although as already mentioned, some traditional animation from the 1940s and 50s was used for reference.

The available prints of the early propaganda cartoons were too badly weathered to be used, so each shot to be re-used had to be completely recreated as vector art in Flash. It's hard to explain this process, but here's a good example of the process:

Here is the original shot:

And here is the re-animated version:

Having the original scene as visual reference was a fantastic asset - however, even with that asset, the re-animated shot still took just over a week to create - so it's not exactly a free lunch. Note that the original footage is scratched, low-resolution (the best copies you'll find for these are between 320 and 640 pixels wide), isn't stable, and is on 12 frames per second. The re-created animation below is playing from a computer, is vector-based (and can be rendered at any resolution without loss of quality), and plays at 24 frames per second.

It was only possible to use a fraction of the old footage in the new film. Approximately 10% to 15% of the scenes in "There's No Tomorrow" are culled from them. The remainder are original, designed to integrate with the older scenes as seamlessly as possible.

In many cases it was possible to do things that would have been too expensive or difficult for the original animators, such as splitting the scenes onto layers and adding parallax and depth to the shots - a process used famously by Walt Disney on Pinnochio, with his "Multi-Plane" camera.

*